The 8 best things to do in Havana

The 8 best things to do in Havana

Traveling to Havana is like stepping back in time, transporting you to the Spanish colonial past with its cobbled plazas and Moorish balconies. The city was founded by the Spanish in 1519 as a trading port because of its natural harbor. Later the town was looted and burned by French pirates. To protect it from marauders and buccaneers the Spanish brought in more soldiers and built fortresses and walls.

The harbor city was a bastion of Spanish seapower in the 17th century, a meeting point for the treasure fleet, the galleons loaded with silver and gold plundered by the conquistadors from the Incas and Aztecs. Merchant ships were docked there waiting to make the perilous voyage across the Atlantic, guarded by warships sailing in convoy back to Spain.

Back in the 1950s, Havana was a place of leisure for tourists who came there for the tropical weather, the casino gambling and the glamor of the late-night clubs. Gamblers were lured by the roulette wheels and card tables, the cocktail lounges and showgirls at the casinos. Havana is a place that has endured in the popular imagination. Here are the eight best things to do in the city.

Walk around Old Havana and have a look at the classic cars, the art deco theaters and the buildings faded by the Caribbean sun. Havana is a sultry city, a place of revelry, the rhythms of salsa, rumba and mambo vibrating in the bars and clubs, the night air scented with rum and cigars. Immerse yourself in the street life and experience the fiestas and dance festivals.

Wander the colonial streets and have a look at the Spanish courtyards, the stone churches, and the worn facades of the buildings. You can walk over to Plaza de la Catedral and admire the Havana Cathedral, a baroque church with frescoes above the altar. Gaze at the ramparts of the stone fortresses and encounter the history of the Spanish colonial capital. Take a sunset walk along the Malecón and look at the pastel colored buildings along the ocean boulevard.

Built during Cuba’s sugar boom the lavish Capitol Building was the seat of Congress until 1959. The Capitol was constructed with block granite and white limestone. It has a design similar to the US Capitol with Doric columns and a dome above the rotunda. The cupola is topped by a replica of the statue of Mercury from the Palazzo del Bargello in Florence.

The granite halls have gilded lamps and marble floors. In the apse is the Statue of the Republic that weighs 30 tons. The statue covered in gold leaf stands on a marble pedestal, wearing a helmet and tunic and holding a shield and lance. The main library has panels made of cedar and mahogany and Tiffany chandeliers. Check out the Venetian mirrors in the Salon Bolívar. Have a look at the Renaissance-style furniture in the Salon Martí. There are guided tours of the building every hour.

Take in a cabaret show at the Tropicana and get transported back to the 1950s. The legendary club opened in 1939 and was frequented by sugar barons, movie stars and crime bosses. Men in white suits and women in mink coats gathered on the dance floor. On a balmy night, you could see Frank Sinatra walking through the glass doors of the casino. Stylish men and women played roulette under crystal chandeliers. The casino was filled with roulette tables and slot machines. Ava Gardner and Errol Flynn drank at the bar and listened to a quartet playing jazz.

Back then the cabaret was produced by Rodney, a choreographer who’d been hired after becoming well known for his live sex shows at the Shanghai theatre. He was a leper who staged fantastic revues at the Tropicana.

He created live spectacles—circus shows with acrobats and magicians, lions and leopards, miniature horses and pygmy elephants. He produced revues where showgirls took the stage, scantily clad in G-strings and feather headdresses.

Rodney had gnarled hands and waddled like a duck. He was unable to dance because his disease made it too painful, but when it came to choreography he was a creative genius. His floor show was a spectacle that showcased contortionists and trapeze artists, elegant women wearing headdresses made of crystal pendants and performers wearing costumes decorated in lace and rhinestones.

Nat King Cole was a headline act at the Tropicana. He wore a white tuxedo, played the piano and sang in English and Spanish. Josephine Baker also performed there. You could see Marlon Brando sitting at a ringside table watching musicians play Afro-Cuban songs. The club was a lurking place for gangsters like Santo Trafficante and Lucky Luciano. Their ambition was to own a chain of hotels and nightclubs in Havana, with Frank Sinatra as the main attraction to lure in the tourists.

Today the club is surrounded by royal palms and acacia trees and the cabaret has the same choreography from the 1950s. At the entrance women are given a rose and men are given a cigar. A hundred dancers perform on the outdoor stage. Included in the ticket price are a glass of sparkling wine, cola, and a bottle of Havana Club rum for a party of four. You can buy tickets to the Tropicana cabaret here.

Plaza de la Revolución is one of the largest public squares in the world. It is the location of Cuban ministry buildings and the National Library. The outdoor square is where Castro spoke to the crowds at political rallies, giving speeches that lasted for many hours. Large rallies were held there on May Day and the Day of the National Rebellion.

Many times Castro spoke to more than a million people in the plaza. He had a deep need to be admired by the masses. In rallying the nation with his speeches, he created a personality cult that inflated his sense of importance. On the facade of the Ministry of the Interior building is the steel outline of Che Guevara, the Argentine revolutionary who was a military commander in the Cuban revolution.

The José Martí Memorial dominates the plaza. Martí was a poet and writer who was killed in a battle during the war of independence against Spain. He is a national hero in Cuba. The memorial consists of a marble statue of Martí seated in a thoughtful pose. Many of his quotes are inscribed on the walls of the memorial. Behind the statue is an obelisk made of granite stone, the tallest structure in Havana, and from its observation floor you get a panoramic view of the city.

Ernest Hemingway lived in Havana on and off for twenty years. He was drawn to Cuba for its deep-sea fishing, its people and low cost of living. He used Cuba as a backdrop for two of his novels and the country honoured him by naming parks, marinas and fishing tournaments after him.

The first stop on the Hemingway trail is Ambos Mundos Hotel, the pink Art Deco hotel on Obispo Street. Take the cage elevator to the fifth floor and walk to room 511 which has been turned into a small museum. Hemingway stayed in this room many times from 1932 to 1939 and it’s where he began For Whom the Bell Tolls, his novel on the Spanish Civil War.

He liked the room for its view of the harbour and Plaza de Armas, a main square in Old Havana. His glasses and typewriter have been placed on a small table. On the floor are his Louis Vuitton travelling trunk and fishing rods. In a glass case on the wall is the telegram sent to Hemingway informing him about winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954. He donated the prize to the Cuban people.

Ten minutes walk from the hotel is La Floridita, the bar where Hemingway was a regular patron. The retro bar with a neon sign is located at the corner of Obispo and Monserrate. Known as la cuna del daiquiri, the cradle of the daiquiri, it was here that the bartender Constante perfected the daiquiri. His recipe includes lime juice, rum, drops of maraschino liqueur and crushed ice. At the entrance of the bar is a giant daiquiri glass.

The place has burgundy curtains and a mahogany bar with iron barstools. Bartenders wearing red jackets and bow ties prepare the drinks. Here you can order the Papa Doble, a daiquiri the way Hemingway liked it with grapefruit juice, no sugar and double rum. They serve 17 kinds of daiquiris, including strawberry, mango, coconut and kiwi. A life-size bronze statue of Hemingway leans against the bar at his regular spot and a ritual daiquiri is placed in front of it every day. On the wall hangs a photo of the writer talking to Castro at a game fishing tournament.

Just outside Havana is the limestone villa Hemingway lived in from 1939 to 1960. It was built in the Spanish colonial style. Now a museum, the house is located on a plantation of royal palms and banana trees. The villa is much the way he left it in 1960 as he planned to return there. You can’t enter it, but you can walk around outside and look through the open windows and doors.

Take a look at the large living room with its original furniture. Hanging on the walls are his personal artifacts from an African hunt, the trophy heads of kudu, gazelle and antelope. There is a sofa and two chairs covered in chintz flower designs. Hanging in the living room is a copy of Gris’s painting The Bullfighter. Hemingway owned the original Cubist painting.

There is a serving tray of liquor bottles on a small table near a sofa chair. Check out the faded labels on his bottles of Cinzano and Bacardi, Campari and Gordon’s gin. At the end of the living room hangs the painting Torro by Roberto Domingo. The painting was made for a poster promoting the bullfights in Valencia and was used in the book cover for Death in the Afternoon.

The bedroom contains wooden chairs and a low bed. Magazines are spread out on the bed. In the closet hangs a brown paramilitary jacket, a fisherman’s vest, and a matador’s jacket. His Royal Arrow typewriter sits on top of a bookcase. Hanging on the wall in his writing room is the mounted head of a Cape buffalo shot when he was on safari in East Africa. There are bullet casings on a large mahogany table.

In the library there are tall wooden bookcases that contain many books on topics ranging from music to natural history to military strategy. There is a large writing table of majagua wood. The wall is decorated with a bullfighting poster and a ceramic plate with the drawing of a bull’s head by Picasso. A leopard skin is spread over a bench.

Take the path by the empty swimming pool to see Hemingway’s fishing boat dry-docked under a corrugated tin roof. The cabin cruiser named Pilar has a black hull and green canvas roof. The cockpit is painted green. On the stern, letters faded from the sun spell out Pilar – Key West. Hemingway often took the boat out on the water. Sitting in a ladder-back chair, he cast his fishing lines to hook and reel in tuna and giant marlin.

Hemingway wrote The Old Man and the Sea while living at the villa. It is the story of Santiago, an old Cuban man who fished the Gulf Stream on a skiff with patched sails. For eighty-four days he had not caught a fish. Then on the next day came the strike of a huge marlin. The fish pulled the skiff far out to sea. When the marlin leapt out of the water he saw how large it was. After a long struggle he reeled it in and tethered it to the boat. But sharks picked up the scent of blood and most of the fish was taken by them in the end.

East of Havana is the small fishing village of Cojimar which was the setting for The Old Man and the Sea. Hemingway kept his boat Pilar here. The old man in the novel was partly inspired by Gregorio Fuentes, the captain of Hemingway’s boat who lived in Cojimar for most of his life. There is an old Spanish fort overlooking the harbor.

In the village there is a memorial to Hemingway built by the local fisherman. A bronze bust of the writer was constructed from the boat propellers they donated. It is located in a small rotunda, a blue pavilion with Ionic columns. There is also a wooden bar and restaurant called La Terraza that overlooks the bay. Hemingway often sat at a corner table there, drinking and eating after a day out at sea. On the wall are black-and-white photos of the writer.

Take a guided tour of the places in Havana connected to Ernest Hemingway.

Stroll along the Malecón

Take a walk along the Malecón, the seafront boulevard that stretches along the coast of Havana. This thoroughfare has a good atmosphere as it is a gathering place for much of Havana, an outdoor lounge where a variety of people come to meet. Take in the colonial architecture as you meander along the walkway, the dilapidated buildings corroded by the ocean air. You can see fishermen casting their lines from the coral outcropping, old men smoking cigars and lovers gazing out at the ocean.

Stop along the way, and if your Spanish is good enough, talk with some of the locals. It’s a great spot to watch the sunset, the glow of the art deco buildings in the fading light. Families sit on the seawall having a picnic meal and young people congregate along the promenade drinking rum and playing guitar. When a cold front comes in the waves crash over the sea wall.

Driving around in a classic car is a great way to see Havana. Cuba’s car culture is a major draw for tourists to the island. It is a rolling museum of American cars from the 1940s and 1950s. With 60,000 of these cars still operating, it’s common to see them driving down the Cuban streets.

After the revolution, Castro banned the import of foreign cars. During the embargo, when the United States cut economic ties with Cuba, there were no American auto parts to repair them. Mechanics had to adapt to keep the cars on the road, scavenging and swapping parts, making repairs using scrap metal. Cuban mechanics are known for their ingenuity. Doing patchwork repairs, they built ‘Frankenstein’ vehicles, using parts taken from Ladas and Volgas, cars that were prominent in Havana during the Soviet era. Things are not as they appear with these cars. Look under the hood of a classic American car and you might find a Chinese diesel engine.

In Old Havana there are vintage cars on display with polished chrome and leather seats. The ones used for city tours are in good running condition. You can have your pick of classic cars to roll in. Cruise along the Malecón in a Cadillac with big fins at the back or a Buick painted in cherry red or bubble gum pink. You can ride through the streets in a Ford Thunderbird with a padded-leather steering wheel. Many of the classic cars are now tourist taxis, having been renovated by Gran Car, a state-run taxi service. Climb into a Chevy convertible and go for a spin with a driver wearing a guayabera shirt and a straw sombrero. Book a classic car tour and cruise the streets of Havana for a couple hours.

Visit the Museum of the Revolution

To get an insight into the tumultuous history of Cuba check out the Museum of the Revolution. The museum chronicles the history of Cuba, focusing on the revolution in the 1950s. The baroque building was once the presidential palace of Fulgencio Batista, the US-backed military dictator. The architecture of the building has a neo-classical style with a banquet room designed to resemble the Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles. The opulent decor includes a white marble staircase, chandeliers and a Golden Hall with walls of yellow marble.

On display in the museum is the gold-plated telephone given to Batista by the US ambassador for promoting American interests. During that time Cuba was a territorial fiefdom of the United States. American corporations owned most of the mines, railways, sugar land and utilities in the country. The economic colonization was made possible by the collaboration of the Cuban elites and the brutal regime of Batista. In one room of the museum is a graphic display of the torture instruments used against dissidents of the regime—the gas torches use to burn the backs of victims, the tweezers used to pull out their nails.

Notice the bullet holes in the marble wall facing the staircase made during the attempted assissination of Batista during the revolution. Museum artifacts include the blood-stained and bullet-riddled uniforms of the rebels killed during the Moncada Barracks attack. The dusty cases contain documents, flags and weapons. There are newspaper clippings, posters and old photos in the exhibit. On display are artifacts from the war like the shirt of Cienfuegos and the beret of Che Guevara. Have a look at the wax figures of Cienfuegos and Guevara as guerrillas trudging through the jungle. Check out the boots and armbands worn by the rebel soldiers.

Displayed outside the museum is a missile that shot down a U2 spy plane during the Cuban missile crisis. There is also a fighter plane of the Cuban air force. Outside the main entrance you can see the Soviet tank destroyer used by Castro in the Bay of Pigs invasion.

Behind the building and encased in glass is the Granma, the cabin cruiser that transported Castro and 81 guerrilla fighters from Mexico to Cuba to launch the revolution in 1956. The boat was built for only 12 passengers. What was supposed to be an amphibious landing turned into a shipwreck when the overloaded boat hit a sandbank in eastern Cuba. The fighters came ashore in waist-deep water and were soon stuck in a mangrove swamp.

Batista’s security forces were expecting them and flew patrols along the coast. The rebels were strafed by war planes. When they reached dry land they took cover in the cane fields and then headed for the foothills of the Sierra Maestra. Many were killed in an ambush by government troops, others were captured and executed.

Che Guevara had joined the expedition as a combat medic. A hardline Marxist, he believed that violence was ‘the midwife of any new society.’ After the ambush the surviving guerrillas dispersed and eluded capture. To avoid detection they walked mostly at night. In Reminiscences of the Cuban Revolutionary War, Che described those first days. ‘We were an army of shadows, ghosts, walking as if to the beat of some dark, psychic mechanism.’

They made contact with peasant sympathizers who led them into the sierra. After sixteen days of wandering in the mountains, Che and the other survivors met up with Fidel at a peasant’s farm. Only sixteen fighters from the Granma expedition made it into the mountains to regroup. The rebels told the peasants how the revolution would bring about change and improve their living conditions. There were few schools and no electricity in the mountains. The peasants lived in dirt-floor huts. Half of them were illiterate. Many had been evicted from their land and were oppressed by the Rural Guard who did the bidding of the big landowners.

The ragged band of guerrillas moved deeper into the mountains. They were always on the move, setting up ambushes on army patrols and attacking isolated garrisons. The peasants taught the insurgents how to survive in their natural habitat, how to blend into their surroundings. They were familiar with the rugged terrain of the Sierra Maestra.

The peasants joined the movement as soldiers, gunrunners and couriers. Supplies were carried by mules up the steep trails. Government troops pursued the elusive guerrillas. The army ransacked and burned villages to dissuade them from joining the rebels. Rebel sympathizers were raped, beaten and executed by Batista’s men.

Che Guevara’s path to the Cuban revolution was a long one and is traced in the book Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life. As a medical student he traveled the length of South America with his friend Alberto Granada, going part of the way by motorcycle and then hitching rides on cattle trucks and river boats, sleeping in barns, garages and police stations. For three weeks they stayed at a leper colony in the Amazon jungle where they treated the patients.

Che started to identify with the farmers and laborers he met on the trip. He saw how the workers were exploited in the tin mines of Bolivia and the copper mines of Chile. Many of the mines were owned by US companies, making Che critical of American foreign policy. He opposed the ‘continental aggression’ of the United States which included CIA-backed coups against left-wing governments in the hemisphere.

In South America the wealth was concentrated in the hands of the Spanish-descended elites while peasants and indigenous people lived in degrading poverty. Che was affected by what he saw on his trip and went through a political conversion. He came to believe in the armed struggle as the only way to bring social justice and equality to Latin America. He drifted to Mexico City where he met a group of Cuban exiles led by Fidel Castro. Fidel told him of his plans to make a revolution in Cuba. Che joined up with the expedition and went for guerrilla training at a ranch thirty miles from the city.

Now in the mountains of Cuba Che worked as a doctor for the peasants who had never been treated by one before. They built a field hospital with a dirt floor. Guevara made sure the hospital treated both wounded guerrillas and enemy soldiers. In the sierra the rebels fought a protracted guerrilla war. Che participated in the firefights in the mountains which were mostly skirmishes. He was known for a reckless bravery when the rebels attacked, looted and burned army garrisons.

Che became the commander of the second column of the rebel army. He enforced strict discipline in his men. There was ‘swift revolutionary justice’ for spies, informers, and deserters. Che meted out punishment for capital offenses. With a clinical detachment he executed the first traitor of the guerrilla band when no one else wanted to do the killing.

Batista’s army launched a summer offensive, a ground assault with ten thousand troops, but it couldn’t penetrate the mountains. The rebels were entrenched in the sierra and fought back against an army that lacked morale and soon the government troops retreated. Fidel expanded the war and sent the rebel army into the plains. Che led an assault on Santa Clara, a strategic town, a transportation hub on the island. There was an intense battle with much street fighting.

Che’s men derailed an armored train carrying federal troops and weapons. The train was taken on by gun fire. Bullets richoteched off the armored plating. The rebels threw Molotov cocktails into the train. They captured bazookas, mortars, machine guns and a million rounds of ammunition. The rebels took over a radio station and attacked a police station. The garrison in Santa Clara surrendered. After the capture of the city, Batista loaded up a plane with gold bullion and fled to the Dominican Republic. The next day the rebels entered Havana and crowds came out to celebrate Batista’s overthrow and the triumph of the revolution.

Guevara was put in charge of overseeing the tribunals at La Cabaña, the Spanish colonial fortress. He was the ‘supreme prosecutor’ in the purge trials at the military prison. Batista’s collaborators were rounded up, given a summary trial and ‘executed by the revolutionary power.’ Many political prisoners were executed under Che’s orders. In the middle of the night they were taken to the wall and shot by a firing squad. There were 500 executions in the first few months of the regime.

Che stayed on in Cuba to work for the revolution. He helped Castro install an autocratic regime where the press was censored and dissent was stifled. For many years he worked as the minister of industry and president of the national bank. He also spent his weekends doing volunteer work, cutting cane, helping to build schools, and digging ditches.

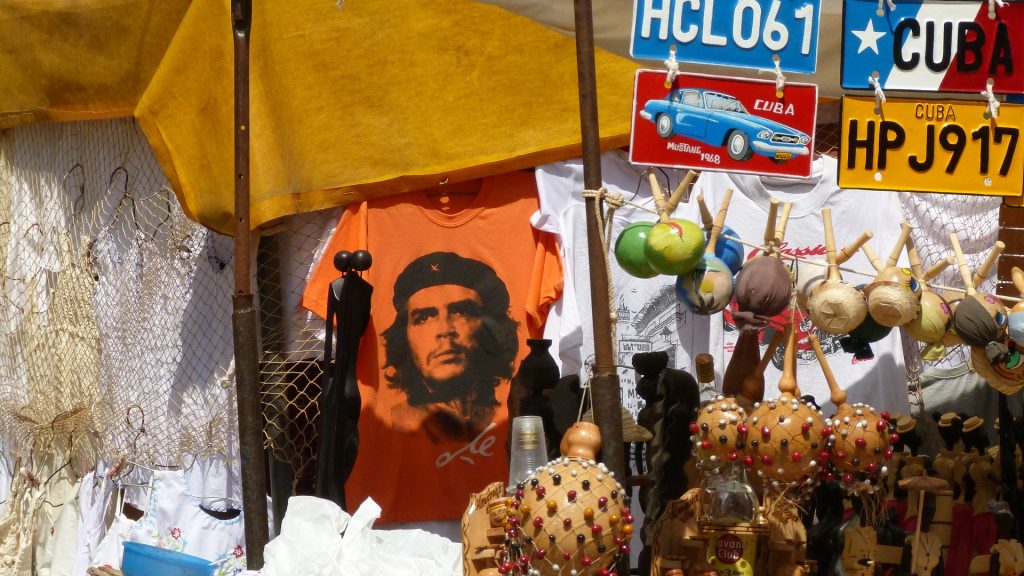

Che believed the Cuban revolution would be the template to spread insurgency in the Third World. Cuba would become a beachhead for continental guerrilla war, setting up training camps for cadres to launch revolutions in Haiti, Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic. Guevara is looked up to in Cuba for being a committed revolutionary. His image can be seen all over Havana, in paintings on murals and billboards, in monochrome graphics on hats and T-shirts.

Che took an interest in the liberation wars in Africa. European colonial rule was coming to an end in many countries on the continent. Congo had gained independence from Belgium in 1960, but the Western powers were now intervening there against the Simba rebellion, a Marxist movement that had taken control of the eastern part of the Congo. The rebels were now fighting against Belgian paratroopers and white mercenaries from Rhodesia and South Africa. Che pledged Cuban support for the struggle and prepared to leave for Africa.

Che led an expeditionary force in the Congo which consisted of two battalions of Afro-Cuban troops. The force was made up of volunteers trained in secret camps in Cuba to support the People’s Liberation Army in the Congo. But they had come too late. The rebellion had been contained. There was low morale among the Congolese troops and they lacked discipline. It was ‘a parasite army which didn’t train and didn’t fight.’ The commanders never came to the front but stayed in Dar es Salaam, drinking, whoring, and driving around in Mercedes Benzes.

Guevara resumed his role as a doctor in the camps, giving the locals penicillin shots and malaria pills. The Cuban troops trained the Congolese in guerrilla warfare. They went out on patrols together and ambushed a convoy of armored cars and jeeps driven by white mercenaries, killing seven of them. The Congolese soldiers believed they were protected by dawa, a magic potion they rubbed over their bodies that made them immune to the enemy’s bullets.

The Congolese command decided to attack a military garrison at Fort Bendera defended by 300 soldiers and 100 white mercenaries. Before the attack the witch doctor applied the magic potion of the dawa on the rebel soldiers. ‘The magical protector was one of the great weapons of the Congolese army.’ During the assault on the fort the rebels were cut down by gunfire. Many refused to fight, others ran away from combat when the gunfire started. There were many casualties. The witchdoctor’s spell hadn’t made them immune to the bullets. He blamed it on women, but there were no women around. Che said, ‘It didn’t look good for the witchdoctor and he was demoted.’

Soon the rebel territory was overrun by government troops in an offensive. Guevara’s base camp was taken. The Liberation Army retreated to the shores of Lake Tanganyika where they were taken across by boats to Tanzania. After the evacuation, Che and his Cuban troops stood on the shores of the lake.

‘Well, we carry on,’ Che said. ‘Are you ready to continue?’

‘Where?’ asked one of his men.

‘Wherever.’

Now Che had to find another place to fight. He couldn’t return to Cuba in defeat as he had resigned from his government posts and renounced his Cuban citizenship. There had been a falling out with Fidel over tensions with the Soviets whom Che had called ‘accomplices to imperialism’ for betraying their revolutionary ideals.

With the aid of the Cuban secret service, Che and his band went on to Latin America. His plan was to start a popular uprising in the mountains of Bolivia. The country would be the launching pad for a continental revolution, a ‘protracted war’ fought on ‘many fronts.’ Che and his men set up a guerrilla camp in the foothills of the Andes. They moved out on foot, setting out on a grueling recon trek that lasted six weeks, slogging through muddy trails, suffering thirst and hunger. There were heavy rains and two men drowned while crossing a swollen river.

The rebels ambushed a Bolivian army patrol and killed seven soldiers. They had been detected and had to abandon their camp. The guerrilla expedition was flawed from the start. They weren’t able to recruit fighters among the local peasants as there’d been an agrarian reform in the country, so many of the peasants were landowners. The rebels didn’t have the support of the Bolivian Communist Party, because Che wanted Cubans to lead the uprising. Some of his Bolivian fighters deserted. Che thought he could replicate the Cuban guerrilla war, but the conditions were not there.

The peasants were frightened of the ragged guerrillas. Che’s identity had become known and the president of Bolivia had brought in American Special Forces to train an anti-guerrilla unit. Bolivian Rangers were being trained by the Green Berets at a base located in an abandoned sugar mill in La Esperanza. The unit was supervised by commandos from the CIA Special Activities Division. After four months of training, the Rangers were inserted into the guerrilla zone to hunt down Che Guevara.

The Rangers pursued the guerrillas, closing in around them. A peasant tipped the Rangers off to the location of Che’s rearguard column and the army set up an ambush. While crossing a river the rebels were hit by machine gun fire in waist-deep water and most of the column was wiped out. Guevara led the vanguard column into a canyon, marching towards the mountains for refuge.

As they marched deeper into the canyon, a local peasant alerted the army which mobilized into the area. The rebels were now trapped in the canyon. The army made its approach. It would take them out at the Yuro Ravine. The guerrillas were now surrounded at the bottom of the canyon. The army took up positions on a ridge above the gully and fired down, unleashing a barrage of mortars and machine guns.

During the firefight Che was wounded and his rifle was hit by gunfire. He was captured by the Rangers and limped back to their base camp with a bullet wound in the leg, a haggard man with matted hair, wearing a dirty, ragged uniform. He was taken to a school house in La Higuera and placed in a mud-walled room, his wrists and feet bound. Blood flowed from his leg wound onto the dirt floor.

A Lieutenant Colonel of the Bolivian army talked with Che, asking him why he had come to his country with a guerrilla band of mostly foreign fighters. Soon after, a radio message came in from Bolivian high command telling them to ‘proceed with the elimination’ of Che Guevara. He was summarily executed, shot five times by an army sergeant. Later his body was transported by helicopter to Vallegrande and buried in an unmarked grave beneath an airstrip.

For two hundred years now, songwriters have composed ballads about revolutionary fighters in Latin America. Vocalists sing corridos of the Zapatista uprising and the Mexican revolution. The Cuban musician Carlos Puebla was known as el cantor de la revolución—the singer of the revolution. He saw himself as a ‘simple troubadour’ and wrote songs in support of the Cuban revolution.

His admiration for Che Guevara inspired him to write Hasta Siempre, Comandante. The song is a response to the farewell letter Che penned to Fidel when he left the country to join the armed struggle in the Congo. The lyrics tell the defining events of the Cuban revolution like the Battle of Santa Clara. The song is performed often by street musicians in Havana and has been covered by many artists including Soledad Bravo, Oscar Chavez and Nathalie Cardone.